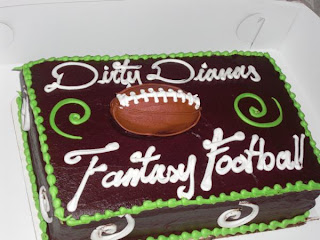

Last Friday marked the inaugural draft party of the Dirty Dianas Fantasy Football League. A small group of women gathered at my homie, Maeg's house to

get drunk

get in on the nerdiest way to watch sports. As the commissioner of this new league, I wanted a few things to happen: our league would be all women, we would throw a party (and there would be cake!), and despite my ophidiophobia, we'd hold a snake [!!!!] draft.

There are a myriad of ways that one can construct a fantasy football league. But, from what I can tell, there are two ways to hold a draft. The most common way is a snake [!!!!] draft, where the first person to draft in round one will be the last to draft in the second round, etc. According to the fantasy experts, though, the fairest way to draft is via auction, where players are ranked, their "dollar" value pre-determined, nominated during the draft process, and auctioned off to the highest "bidder." Yes, you read that correctly.

I know, I know. LeBron's infamous decision last summer stirred up incredible controversy, including discussions about whether or not multi-million dollar athletes could liken themselves to slaves. Indeed, professional sports is not chattel slavery, but the lexicon of slavery remains hauntingly useful for those who talk about sports. One need only follow scouts on Twitter during the NFL combine--the "audition" many college football players participate in before the actual draft--to understand what I mean. But in case you missed those tweets last spring, the language around fantasy football helps illustrate, too.

If you peruse ESPN's fantasy football rankings, for instance, you will find a dollar amount next to each name on the list under the heading "Auction." Of the top fifteen players, 14 are black. In a league where 65% of the players are black, the ease with which commentators and fantasy fans employ the language of slavery is chilling. Fantasy football participants love to talk about the players they own. Yes, own. Listening to a fantasy football podcast for just a few minutes in, say, October, will yield discussions of trade value and whether or not a player is equal to another. Now that I have successfully uploaded the team rosters on to our site, any member of the Dirty Dianas can edit her trading blockby marking whether a player is "on the block" or "untouchable." Clearly, folks who play fantasy football are not engaging in the real life buying and selling of other human beings. Yet the language that helped vivify that institution resonates in the realm of the NFL draft and in the region of fantasy football.

And most of us use it with such ease.

Perhaps we should slow the impulse to criticize players when they say that they are being treated like slaves when the language we deploy to describe them seems to suggest that we view them as such. If someone talked freely about my wingspan and flight time, I might occasionally imagine that I am a bird. So, although we know that professional sports does not require plantation work, we still must wonder how quickly that point is obscured as players are paraded in front of team representatives and measured for their brute force and (natural) athletic ability so that their value can be determined. How stringently can we chastise Adrian Peterson for saying he's treated like a slave when ESPN has his auction value starting at $59? It seems to me that if he is ridiculous, so are we for not checking each other for so glibly hanging around the water cooler talking about who we own in our fantasy league. I cringe at the fact that looking for a job in academia is described as going on the market. How many fantasy football team owners twittered similarly problematic and obnoxious words about their ownership of Arian Foster to Arian Foster when he hurt his hamstring the other day? I cannot imagine the number.

This language is not necessary. Rather, it is the residual effect of a capitalistic society that reduces humans, particularly black humans, to tools or commodities whose value is purely determined by (white male) gazers, whether the stakes are actual or fictional. If we can call out millionaire players for their hyperbole, then surely we have the ability to check our own language and interrogate the ways that the words we use show what, who, and how we value.With the popularity of fantasy sports reaching well beyond the realm of nerdy white boys, it seems time we highlight the language we use when we play. After all, games both reflect and teach us about culture; what does the language of fantasy sports, then, tell us about the reality of ours?

P.S. Happy birthday, Michael Joseph Jackson

No comments:

Post a Comment